Re-Engaging Students in the Learning Process

Blog post by Robert Low based on this edLeader Panel

Now that the third school year in a row has been disrupted by COVID-19, many students are struggling with academics and other issues that make it difficult for them to focus fully and enthusiastically on learning in the classroom.

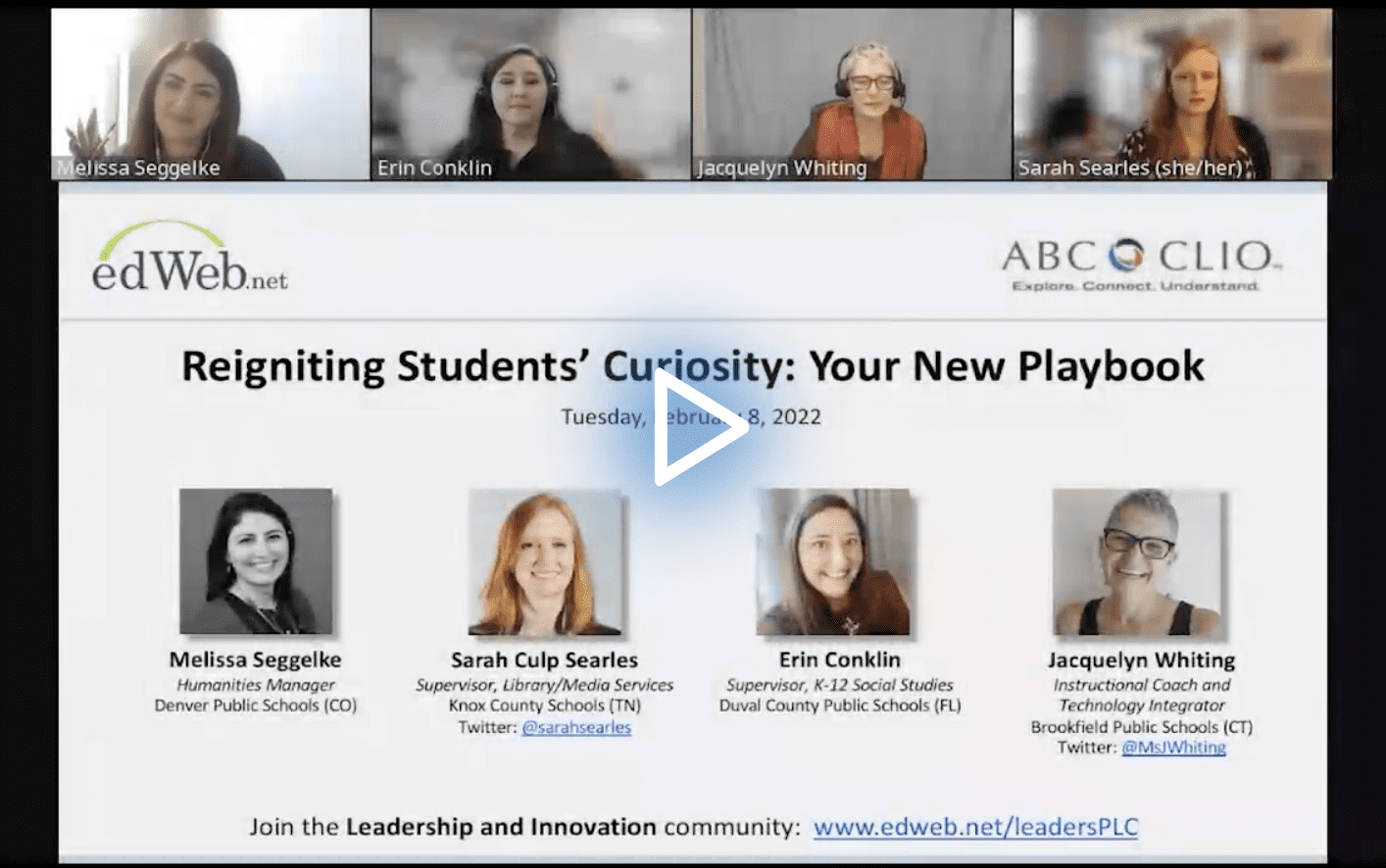

During a recent edLeader Panel, district administrators from across the U.S. along with Jacquelyn Whiting, an instructional coach and technology integrator for Brookfield Public Schools (CT), discussed ways to make in-school learning more engaging for today’s students.

During the session, Whiting cited a recent report on students who had been achieving high grades before the pandemic but now are just receiving average grades. Many of them reported a priority realignment in which grade motivation has been replaced by a desire to focus on authentic “passion projects.” This shift often began during remote learning, when the students had more time and freedom to work on projects that were personally meaningful.

Erin Conklin, Supervisor of K-12 Social Studies for the Duval County Public Schools (FL), also noted this trend, saying that some students who didn’t have teachers or parents present while learning remotely had started doing research projects online and collaborating with their peers, but with the return to face-to-face learning, the time and inclination for that sort of work had been lost. Other students, meanwhile, were continuing to pursue their interests by using online apps such as Instagram and TikTok.

Providing Time and Space for Student Inquiry

Sarah Culp Searles, Supervisor of Library Media Services for Knox County Schools (TN), pointed out that many teachers don’t feel they have room in the curriculum for curiosity-borne projects, especially when there is an emphasis on teaching efficiently, generating high grades, and sticking to a schedule. To create an environment in which a more student-driven process is safe and okay, there needs to be time in the curriculum pacing guide or set aside in other ways to explore resources and try out ideas that may not turn out to be right.

One of the best ways to achieve this is through “backward design,” which starts with a focus on the final goals of a course or unit, but then builds in time for projects aligned with students’ curiosity and interests. In many districts, these types of inquiry projects are now being built into the curriculum as a means of engaging students in the learning process and enabling them to learn in ways that are personally motivating and meaningful.

A classroom full of students working on a variety of projects in different ways may result in a lot of talking and moving around. Conklin recommended making sure that administrators understand how this type of work can engage students and result in their taking ownership of learning, because the different types of activities taking place at the same time can look like a lack of classroom management.

Melissa Seggelke, Humanities Manager for Denver Public Schools (CO), discussed the importance of explicitly teaching students the art and skill of asking questions as part of this process, so students know how to start with brainstorming but then can hone their questions in collaboration with others in order to refine their learning process and obtain final answers. She mentioned one teacher who posted students’ questions on a classroom wall and then would refer to the questions when lessons or classroom discussions overlapped with them.

Integrating Resources with Student Inquiry

The pandemic-driven shift to a new paradigm, in which most students have computers and are comfortable using them, can result in greater access to primary and secondary sources that become a focus of learning, rather than just having the teacher provide information. And many students can now use collaborative tools to facilitate their work with classmates on inquiry projects.

Searles believes that textbooks can and should be used in new ways, such as serving as “inquiry frameworks” and as an equitable source of content knowledge, guidance, and support. She also recommends viewing school librarians as educators who can support student inquiry through their ability to curate resources, help students find their own sources, and continue their research throughout an inquiry project.

Finding and interviewing local experts can also be a way for students to explore relevant topics in an interactive and interesting way, especially if this type of work is combined with tours or field trips that add context and lead to a deeper, firsthand understanding of an issue. This type of experiential learning can also be turned into a video that becomes part of a project’s documentation or final presentation.

Communicating the conclusions of a project in an authentic and meaningful way is another valuable part of the process, as it can give students a sense that what they have done is of value to others, while further developing their communication skills. That type of experience can then motivate students to continue their learning through new inquiry projects.

Learn more about this edWeb broadcast, “Reigniting Students’ Curiosity: Your New Playbook,” sponsored by ABC-CLIO.

Watch the Recording Listen to the Podcast

Join the Community

Leadership and Innovation is a free professional learning community on edWeb.net that serves as an online forum for collaboration on leadership and innovation in schools to meet the needs of the next generation.

For 65 years, ABC-CLIO has been providing reference, nonfiction, online curriculum, and professional development to inspire life-long learning for today’s students and educators. ABC-CLIO is a recognized leader in the field, providing print and online materials for learners, researchers, educators, librarians, and information specialists worldwide.

For 65 years, ABC-CLIO has been providing reference, nonfiction, online curriculum, and professional development to inspire life-long learning for today’s students and educators. ABC-CLIO is a recognized leader in the field, providing print and online materials for learners, researchers, educators, librarians, and information specialists worldwide.

Comments are closed.