Building Bridges Between Literacy Development Practices

Watch the Recording Listen to the Podcast

They call them the “reading wars”—divisive debates about the “best” approach to developing foundational reading skills. But there doesn’t have to be an all-or-nothing solution to helping young children learn to read and write with competence and pleasure.

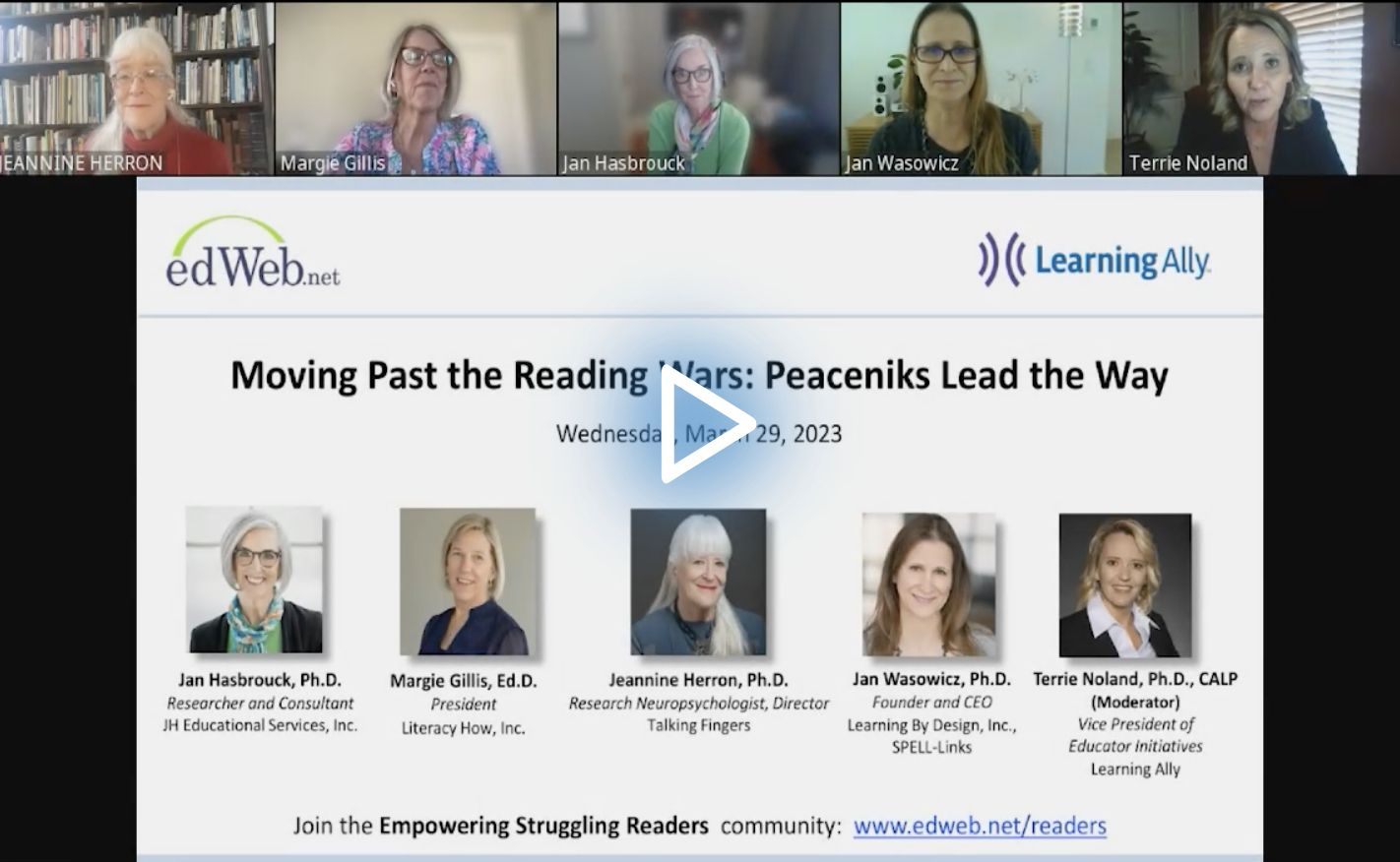

Practitioners can come to a consensus on strategies to end the divisiveness, explained reading experts on the edLeader Panel, “Moving Past the Reading Wars: Peaceniks Lead the Way.”

The panelists (members of the “Reading Peaceniks” who bring together literacy education researchers and practitioners to realize similarities among reading development methods) highlighted the viewpoints, priorities, and commonalities among literacy disciplines to underscore where the “twains” meet, with a focus on early literacy.

Building Bridges

Only one-third of children are learning to read proficiently, a concern leading to much talk about reading (the Science of Reading, reading research). Thus, conflicting points of view about whether to develop foundational reading skills or reading comprehension.

With the different reading camps, misinformation, miscommunication, and misunderstanding (and even mistrust) cloud overlapping goals and strategies. Maybe practitioners use the same terms to mean other things or different terms to mean the same thing.

Focusing on common priorities is essential to build learners’ reading proficiency. That means having a shared understanding of the meaningful ways to provide children with oral language development and the alphabetic coding that research shows are necessary for developing joyful readers and writers.

According to the Peaceniks, who focus on essential components of instructional approaches at their earliest roots (PreK to Grade 1 or 2), bringing together disparate practices is possible. Having found consensus among 35 literacy practitioners and researchers, the group produced Print-to-Speech and Speech-to-Print: Mapping Early Literacy, a paper summarizing the most crucial early instruction.

Critical Concepts

Literacy, contend the Peaceniks, is much broader than reading. It’s about reading and writing. First, there are foundational skills for decoding and encoding and writing and spelling words. The approaches are integrated and have many commonalities. Then there are higher-level language components for meaning—reading comprehension and expressing meaningful ideas and thoughts in writing. Foundational spelling skills enable that competency.

The different reading camps recognize that reading and writing start with language literacy processes that connect to the meaning of a word, giving it context as foundational literacy skills are developed. Effective literacy instruction builds on words that children often hear in their early years, helping them to, for example, write words, build their vocabulary, and use sentence structure.

Complementary Approaches

Encoding is a critical first step in literacy development. It ultimately builds decoding skills that lead to reading and writing proficiency and enables phonemic awareness.

When learners encode, they think about a meaningful spoken word and figure out the parts (segmentation) that form it. Words are hard to cut into separate pieces, but when a word is said, students can think about its sound and what makes their mouths move when they say it. Over time, this process becomes automatic. Encoding and going from speech to print further promotes phonological phonemic awareness.

Decoding alone does not lead to phonemic segmentation. For example, a learner might read and decode a word’s first letter or letters (putting sounds with letters) and then guess the rest of the word. That approach interferes with learning how to read. Encoding to decode involves using a recognized grapheme-phoneme pair.

A speech-to-print approach doesn’t just teach spelling, nor does it ignore decoding. It teaches reading through the foundational skills of decoding through encoding. Research has shown that if children learn how to spell words (compared to learning how to decode them), they improve in spelling and decoding. The foundational skills they develop transfer to other reading patterns.

In brain studies of pre-literate children (age four), one group of students traced over the letters. Another group saw the letter and copied it. Finally, the third group was shown the letter and found it on the keyboard. The students who wrote the letter showed greater normalization of the reading writing circuit in the brain than those who just traced or keyboarded.

Research offers insight into this finding. Students might spend more time on tasks when they write by hand rather than decode. Encoding requires attention to the orthographic detail of those words. Reading doesn’t require that same attention to orthographic detail.

Diversity of Understanding

While practitioners may fall into one reading camp, there is no reason to remain in that camp to help young children learn how to read. Instead, it’s critical to come to the table with a diversity of understanding, recognizing where literacy instructional practices are similar and how they can complement one another to support the development of young children’s reading and writing skills.

All practitioners can agree that they do not want children to struggle with reading later in life.

Learn more about this edWeb broadcast, “Moving Past the Reading Wars: Peaceniks Lead the Way,” sponsored by Learning Ally.

Watch the Recording Listen to the Podcast

Join the Community

Empowering Struggling Readers is a free professional learning community that provides educators, administrators, special educators, curriculum leaders, and librarians a place to collaborate on how to turn struggling readers into thriving students.

Blog post by Michele Israel, based on this edLeader Panel

Comments are closed.