Redefining Workforce Technology: Learning and Employment Records

Watch the Recording Listen to the Podcast

With the ubiquity of the internet, there have been various iterations to the resume and portfolio development for job seekers—and to the recruitment process for employers. From the documentation of skillsets to the way that resumes are shared, there have been positive changes to the process that have allowed those searching for a job to make it easier for employers to find them.

While these changes have been a step in the right direction, a new approach is being developed to revolutionize how job seekers and employers find one another. Learning and Employment Records (LERs) is an emerging technology that is redefining how job seekers search for the right fit and how employers find people with the right skillsets to meet their needs.

Over the last year, Digital Promise, a national education nonprofit, teamed up with workers in frontline sectors along with leaders in higher education, business, and technology to center end-user experiences and mitigate biases in the design of LERs. In the edLeader Panel, “Learning and Employment Records: What Educators Need to Know About This Emerging Technology,” Antionette Miller, Project Manager of Adult Learning at Digital Promise, led a discussion about the research and development of LERs and the results that have been experienced by participants in the pilot phase of the program.

What Are LERs and Why Are They Important?

According to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation’s T3 Innovation Network, an LER is “a comprehensive digital record of skills and competencies learned in school, on the job, through volunteer experiences, or in the military. It includes credentials, diplomas, and even employment history.” A comprehensive LER positions the owner to better identify training opportunities, explore career paths, and apply for jobs.

In 2018, Digital Promise began to research the career pathways available to frontline workers. The research revealed that processes and systems in the adult learner/worker ecosystem did not support the flow of data between stakeholders and frontline workers. Expanding on that research, in 2019 they published Building Networks for Frontline Talent Development, which focused on the promise of data interoperability to “promote a more collaborative, data-driven, and learner-centered education and workforce ecosystem.”

A key finding of the report was that fragmentation in data systems prevents people from having agency over their learning and employment data. Another finding was that education and career service providers have limited capacity to collect and track longitudinal data outcomes for learners and workers, including those who may have exited a training program before completion, leaving them unable to evaluate their needs.

These key findings drove Digital Promise to develop a program that directly included frontline workers in the design and development of LERs to ensure they can document and access their experiences in a way that would provide a full portfolio of their skills and talents to future employers.

Inclusive Design Principles

Inclusion of workers in the design process increases the likelihood of a more equitable design, adoption, and use. Working in partnership with the T3 Innovation Network, a set of inclusive design principles was created with the goal of centering the user experience while also eliminating any racial biases that could be built into the design.

To create the principles, they collaborated with participant advisors (workers in frontline sectors) as well as leaders in higher education, business, and technology to co-design and communicate the value of LERs. The result of this collaboration is the recently published report, Inclusive Design Principles for Learning and Employment Records: Co-Designing for Equity.

Four key elements were used for the design framework for the collaboration. These elements include:

- Inclusive Design: Sessions held with 30 workers in frontline sectors who were paid consulting rates.

- Iteration: Collaborative sessions with LER technical experts and pilot platforms to develop and iterate on inclusive design principles and user profiles.

- Evaluation: A survey of key stakeholders, including workers, for feedback on potential LER value, use, and implementation.

- Communication: Sharing the principles publicly and highlighting, via video, learner perspectives.

The sessions with frontline workers generated a lot of different ideas related to accessibility, discrimination, and the value of the technology. One activity that was used to engage the workers was a Jamboard that asked them to reflect on their work experience from their perspective and the perspectives of others.

This activity helped them to describe their skills and experiences in a way that may not be evident or clear from looking at their job titles or even job descriptions. For example, one participant advisor said, “I deal with all types of people every day,” and so clearly that was someone who has experience with listening, managing conflict, and cultural competence. This activity allowed the participant advisors to share their personal experiences navigating the workforce and education systems.

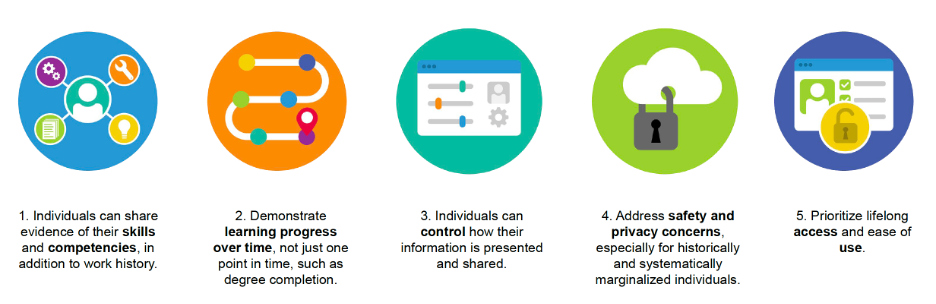

Based on the themes that emerged from the design sessions with frontline workers and a broader survey that was conducted among 315 participants, Digital Promise identified five design principles to drive the development of LERs.

The edLeader Panel presenters also shared a video showcasing the experiences of participant advisors. Participants ranged from a cook in a restaurant to a UX researcher to a program manager for a nonprofit to someone completing their associate degree. One of the participants said the exercise of creating an LER “made me understand myself a little bit better, too, as far as where I wanted to go with my career path.”

Eliminating Inequities in the Hiring Process

Sarah Cacicio, Director of Adult Learning at Digital Promise, explained that a driving concern in the development of LERs was to eliminate systemic inequities in the hiring process. She says they believe that “LERs have the potential to mitigate some of the bias and discrimination that we see in current hiring practices.”

In the pilot program, some of the participant advisors shared struggles they encountered navigating both the education and workforce systems. For example, some felt that the inclusion of their name in an LER invited discrimination because they felt employers might be biased against those with ethnic names. Others shared that not having a degree, even if they had the skills required, presented inequities in the hiring process.

Cacicio also pointed to participants who had gaps in their resumes—gaps that could occur for any number of reasons—even though they continued to have life experiences and build skills to qualify for a job. With all these challenges in mind, the focus of LER creation became to build a portfolio of the whole person—what he or she can do—not just how a person might meet a job description. The LERs, therefore, become a reflection of real-life experiences and should be designed with those experiences at the forefront.

Designing to Meet the Need

Malliron Hodge, Design Consultant at her company MLH Innovation Consulting, worked directly with the participant advisors during the collaborative sessions. For her, starting with the community piece to connect similar stories and experiences was important. Once those experiences and themes were established, she said the next step was to identify the need because they want to make sure they are addressing “a root cause of the need that exists with frontline workers.”

Hodge shared that the designers working with the participant advisors were careful not to make assumptions about needs. They relied on the experiences of the participant advisors to drive the design of LERS. In short, she said that they “started with community, we shared those similar needs and stories, got deeper on the needs around root cause, and then moved to the space around what this could look like to address the needs they were currently experiencing.”

Panelists and participant advisors, Soraya Francois and Vontrese Washington, discussed how the process changed how they viewed their past job experiences and how the exercise of creating an LER helped them to better position their skills and assets.

For Francois, it provided an opportunity to re-evaluate how she built her resume. In the past, she said, “I always used my position description and just pasted that on my resume.” After going through the process, she shared that she learned, “there were things I did, and skills I had, that were not on the position description that were important to highlight.”

Washington agreed with Francois’s conclusion and shared that learning how to create an LER gave her ownership over the resume-building process and actually took resume building to a new level, which she felt provided a better way for her to present herself to future employers.

Importance of LERs in Education

While the focus of LER creation has centered around frontline workers, Digital Promise and their partners at the T3 Innovation Network believe that the design and creation of LERs can start in secondary education as students begin to build their skillsets and work experience.

Having a digital record that captures all their experiences can teach them how to best present themselves for college and career opportunities. This emerging technology can be leveraged by school counselors, workforce development coordinators, career service providers, and teachers to help students prepare for a skills-based economy.

Furthermore, an LER is a great tool for teachers to use to capture their PD experiences, CEUs, and other microcredentials. In their last report, Digital Promise includes information about an emerging Teacher Wallet that teachers will own and manage. As influencers of young people, it is important for educators to be aware of LERs and how they will shape the future of employment.

Highlighting Skills in a Gig Economy

In the new gig economy, skills and abilities go beyond a degree or certification. Capturing and highlighting those skills to provide a full picture of a person’s capabilities will be critical for both workers and employers to meet the demands of the increasingly monetized digital world.

Presenting the tangible skills that have been obtained through multiple experiences—personal life, country of origin, part-time jobs, online experiences (think Etsy, Poshmark, YouTube channels, blogs, etc.), certifications, software programming, etc.—should come first to demonstrate a worker’s ability in a skills-based economy.

The collaborative partnership between Digital Promise and the T3 Innovation Network is off to a promising start. The Network’s LER Resource Hub has more information on the pilot programs, best practices, and how to contribute to LER design.

Learn more about this edWeb broadcast, “Learning and Employment Records: What Educators Need to Know About This Emerging Technology,” co-sponsored by Digital Promise and Walmart.

Watch the Recording Listen to the Podcast

Join the Community

Career, Technical, and Adult Education is a free professional learning community where educators, community leaders, and other stakeholders can share information about helping students and adults acquire the academic and technical skills needed for high-skill, high-wage, and high-demand occupations in the 21st century economy.

Blog post by Ginny Kirkland based on this edLeader Panel.

Comments are closed.